Tell Me I Didn’t Choose This

I’ve lost touch with some of the people I used to be. I’ve yet to hear from the person I will become.

The saying goes we contain multitudes. These multitudes, however, are funnelled into a singularity. A single life in a single body holds a constellation of experiences and possibilities that remain unfulfilled. They are the food that feeds the multitudes, they feed the people you could yet be, or that you already are and you somehow disguise. Bury, cloak, until they fall asleep. A shift and something changes, stirs, awakes. At times these alternate lives remind us of who we were. At other times they illuminate the future. They can become deep whispers, quiet hauntings. Questions planted. Sometimes for ourselves, sometimes for others, sometimes perhaps for following generations. Shifting faces that are glimpsed by those who, in time, find a way to get close. Who else are we holding on to? How many variations of yourself are you aware of? How radically different are they from the person that your friends, lovers and family know? What is the relationship between the life lived and the lives un-lived? I began making work through these questions, knowing that I am different versions of myself to different people. Knowing that I am different people to myself, sliding between my layers of selfhood all the time. In doing so I began with a slice of my experiences, some fundamental ones we all share a version of.

Our bodies come to be sites of success, sites of release, of joy, pain and awkward delusions. They hold us, sweating out our visions of ourselves and subtly, remorselessly changing day after day. My body arrived jaundiced and curiously marked between my legs. A deep purple angioma made of a web of vessels that can burst and pour with blood at any moment. The jaundice placed me in an incubator for a week or so, my life starting in a tiny tank. Around the age of 6 or 7 the angioma began to be a source of humiliation at school. I began to learn about the body as a site of shame. From then it became the keystone in a decade or so of bullying at school. As that faded sometime in my later teens I was left with the more banal failure of this body, the bleeding from between my legs without warning, contending with the possibility of any moment being one where I have to find somewhere, a bathroom, where I can just let myself bleed until it stops. Blood can pour from between my legs in my sleep. Running for a bus. Eating with someone I barely know. On a stage in the middle of a performance. It does it’s own thing and I have to - the cliche is apt here - live with it. Anywhere, anytime, no warning.

And then another layer that spreads sloppily on top of that. The connection to my sexual organs and a wider identity that feels both undermined and something to hold on to. Both sad and remarkable in its own way. There isn’t much I can do. There is no sanitary towel, no tampon for men and the surgery required to help would be invasive and disfiguring. The age at which there was an understanding that we are not all what we may seem was young for me. I was a person that had another person underneath, and probably another person underneath that. Learning this helped me see that what we believe and the sense of who we are is slippery, a function of scales rather than categories. Who you are is not who we see. How do you reconcile the parts of you that feel feminine to the parts that feel masculine? How do they mutate and talk to one another over time? How do you feel like expressing this? Perhaps in your body language, perhaps in your tastes, perhaps in who you choose to talk to and how you open up? These are questions I have been lost in for many of my years. It feels sometimes that I have two bodies: the one that others know and the one that I know. The one with the hard shell, that could resist any insult, or the oozing, frail, messy one, always slightly lost between points.

The next plank to who we are is a result of the environments we find ourselves in. I recall my childhood homes with some joy, they were rough around the edges in a way I will always feel grateful for. I grew up mainly on the Archway Road in North London. The building had been an empty, sometimes squatted terrace house that my parents managed to rent cheaply from ACME, the artist tenancy organisation. After a long battle against the road being widened the tenants of that row managed to claim a form of squatters rights and bought it from the Department of Transport for not much more than the price these houses cost to build. A price, miraculously, many could afford to borrow. The neighbours were a good mix. On one side we had Denzel, a man who radiated a deep warmth and a very forgiving kind of attention towards me. You couldn’t do any wrong with Denzel. His daughter Tamla was one of the few babysitters I ever had. She had to cope with the devastation of her father getting jailed for dealing crack. On the other side there was Bill, an old Trinidadian who had been drafted into the RAF during the war. His attention to me was built on exhortations. Don’t smoke (he did, too much.) Listen to calypso. Don’t play football, play cricket. What do they teach you at school these days? Whatever you do around here watch out for the glass! His garden, much of it glass, was his pride and joy. The pots and beds were a miniature warren built from street finds and old fridge shelves. Scuffed hubcaps decorated baskets. Beyond them were more artists who had landed there in similar circumstances. Vietnamese and Philippino families whose houses were places I could occasionally play in, Phil and Steve - the Diggle brothers - one of which painted and the other played guitar for The Buzzcocks. Carlo and Eddie were potters whose house was their studio and whom I idolised. The people on my street made up for a lot that wasn’t easy environmentally. They were generally caring people. It didn’t become clear until later school years exposed me to the wealth of the surrounding areas, disparities that children latch onto, that there were difficult inequalities here, inequalities that were clawed in cruel playgrounds. My home became a home that I felt ashamed to share. It wasn’t the same as the houses of newly made friends. It became a crooked shadow of these cushy, carpeted exercises in North London prosperity.

And then there are the experiences that just rain upon us. These are the fences that funnel us, the traps that we get snagged in, the opportunities which alter things for the better, that we learn from, that introduce us to the people who help us and who abuse us. Here my life is a patchwork that is common for many of us. My pre-teen years were often disrupted with a chronic fight with asthma. The periods in hospital, out of school, fuelling a failure to settle and connect with other kids. But those periods also offered long stretches of time to read, and draw, and stare at things. Going into my teens I felt my ability to love change. At that moment the connection between desire and gender felt irrelevant. Looking back I see a messy, half-formed sense of bisexuality that was drip-fed in places and attacked in others. The openess in me was shattered by molesting advances I faced in the hands of a man who ran the firm that controlled the security for much of the retail and nightlife in the West End. It was years before I understood what this assault had done to me and the place of fear it had pushed me into when it came to male intimacy.

I remember that point when I wanted a treehouse. When so much of play is about making dens. Hideaways. Cosy, private spaces to take a little protection and let your world form and grow. I remember making little flat circles to lie somewhere in the long grass. Tiny structures out of cushions I could just put my head in and daydream. Sheets, blankets, cardboard and dusty corners. Books, stories, drawing and later music. My parents gave me many tools with which to make these spaces, kindling a creativity. Thinking back now I see the tree house as a metaphor for much of my childhood. It is rickety, patchy, the rain gets in and it doesn’t feel particularly safe. But the tree in which it sits is strong and sturdy. In my head that tree is my mother. So many of these lumps in life were soothed by her strength. She saw me early on and prepared me to be myself. I write this on a train, the window framing the drowsy green of England, and I remember sitting on a similar train with similar views, mum asking me what I was being called in the playground and did I know what those words meant. On that train she taught me a laundry list of abusive queer terms and told me that I should never let these words hurt me. That the people who used them knew nothing of love and little of themselves. I wish she had been right but they served the purpose the kids intended, to ostracise, to give short-term strength and immediate power to those bullying their way through the shitscapes of school. And in this lay another lesson. That no matter how much our kin love us, they cannot protect us from the pain that is one of the currencies of life.

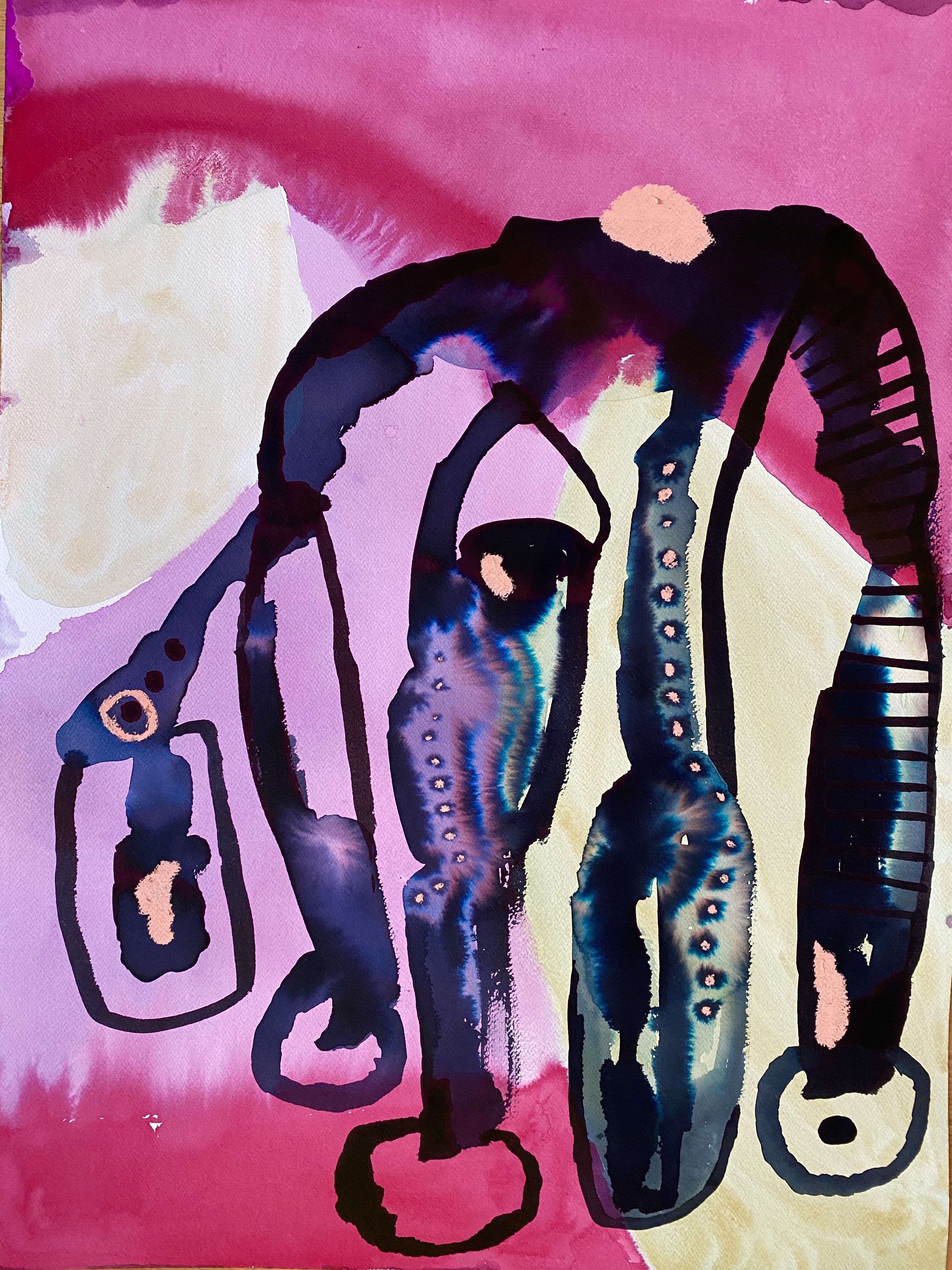

Whatever school is, it hammers something into us. That kids now have had to become a little more understanding of the world of identity, violence, sex, climate catastrophe and so much else fills some adults with sadness at supposed lost innocence. It fills me with hope that those playgrounds I so hated have become a little softer. A little kinder. I see the space growing for increasingly younger people to move through their multitudes with more ease and grace and wonder. Their joy less clipped, their light less dimmed. Lives in which tarnished marks can be worked on, buffered with conversations and understanding. It is a sense of these planks and paths, bodies sliced and diced into whatever shape they become. Bodies of pain, hope and colours. This is what I try to summon with the pens, inks and paper I have used over the last few years. I have been lucky to have been given these spaces and chances to let myself out over the years. Every curious circumstance that my life has produced, from the bleakest to the most glorious is one I am grateful for. The people I’ve yet to become are here, alongside those that never materialized.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I’ve lost touch with some of the people I used to be. I’ve yet to hear from the person I will become.

The saying goes we contain multitudes. These multitudes, however, are funnelled into a singularity. A single life in a single body holds a constellation of experiences and possibilities that remain unfulfilled. They are the food that feeds the multitudes, they feed the people you could yet be, or that you already are and you somehow disguise. Bury, cloak, until they fall asleep. A shift and something changes, stirs, awakes. At times these alternate lives remind us of who we were. At other times they illuminate the future. They can become deep whispers, quiet hauntings. Questions planted. Sometimes for ourselves, sometimes for others, sometimes perhaps for following generations. Shifting faces that are glimpsed by those who, in time, find a way to get close. Who else are we holding on to? How many variations of yourself are you aware of? How radically different are they from the person that your friends, lovers and family know? What is the relationship between the life lived and the lives un-lived? I began making work through these questions, knowing that I am different versions of myself to different people. Knowing that I am different people to myself, sliding between my layers of selfhood all the time. In doing so I began with a slice of my experiences, some fundamental ones we all share a version of.

Our bodies come to be sites of success, sites of release, of joy, pain and awkward delusions. They hold us, sweating out our visions of ourselves and subtly, remorselessly changing day after day. My body arrived jaundiced and curiously marked between my legs. A deep purple angioma made of a web of vessels that can burst and pour with blood at any moment. The jaundice placed me in an incubator for a week or so, my life starting in a tiny tank. Around the age of 6 or 7 the angioma began to be a source of humiliation at school. I began to learn about the body as a site of shame. From then it became the keystone in a decade or so of bullying at school. As that faded sometime in my later teens I was left with the more banal failure of this body, the bleeding from between my legs without warning, contending with the possibility of any moment being one where I have to find somewhere, a bathroom, where I can just let myself bleed until it stops. Blood can pour from between my legs in my sleep. Running for a bus. Eating with someone I barely know. On a stage in the middle of a performance. It does it’s own thing and I have to - the cliche is apt here - live with it. Anywhere, anytime, no warning.

And then another layer that spreads sloppily on top of that. The connection to my sexual organs and a wider identity that feels both undermined and something to hold on to. Both sad and remarkable in its own way. There isn’t much I can do. There is no sanitary towel, no tampon for men and the surgery required to help would be invasive and disfiguring. The age at which there was an understanding that we are not all what we may seem was young for me. I was a person that had another person underneath, and probably another person underneath that. Learning this helped me see that what we believe and the sense of who we are is slippery, a function of scales rather than categories. Who you are is not who we see. How do you reconcile the parts of you that feel feminine to the parts that feel masculine? How do they mutate and talk to one another over time? How do you feel like expressing this? Perhaps in your body language, perhaps in your tastes, perhaps in who you choose to talk to and how you open up? These are questions I have been lost in for many of my years. It feels sometimes that I have two bodies: the one that others know and the one that I know. The one with the hard shell, that could resist any insult, or the oozing, frail, messy one, always slightly lost between points.

The next plank to who we are is a result of the environments we find ourselves in. I recall my childhood homes with some joy, they were rough around the edges in a way I will always feel grateful for. I grew up mainly on the Archway Road in North London. The building had been an empty, sometimes squatted terrace house that my parents managed to rent cheaply from ACME, the artist tenancy organisation. After a long battle against the road being widened the tenants of that row managed to claim a form of squatters rights and bought it from the Department of Transport for not much more than the price these houses cost to build. A price, miraculously, many could afford to borrow. The neighbours were a good mix. On one side we had Denzel, a man who radiated a deep warmth and a very forgiving kind of attention towards me. You couldn’t do any wrong with Denzel. His daughter Tamla was one of the few babysitters I ever had. She had to cope with the devastation of her father getting jailed for dealing crack. On the other side there was Bill, an old Trinidadian who had been drafted into the RAF during the war. His attention to me was built on exhortations. Don’t smoke (he did, too much.) Listen to calypso. Don’t play football, play cricket. What do they teach you at school these days? Whatever you do around here watch out for the glass! His garden, much of it glass, was his pride and joy. The pots and beds were a miniature warren built from street finds and old fridge shelves. Scuffed hubcaps decorated baskets. Beyond them were more artists who had landed there in similar circumstances. Vietnamese and Philippino families whose houses were places I could occasionally play in, Phil and Steve - the Diggle brothers - one of which painted and the other played guitar for The Buzzcocks. Carlo and Eddie were potters whose house was their studio and whom I idolised. The people on my street made up for a lot that wasn’t easy environmentally. They were generally caring people. It didn’t become clear until later school years exposed me to the wealth of the surrounding areas, disparities that children latch onto, that there were difficult inequalities here, inequalities that were clawed in cruel playgrounds. My home became a home that I felt ashamed to share. It wasn’t the same as the houses of newly made friends. It became a crooked shadow of these cushy, carpeted exercises in North London prosperity.

And then there are the experiences that just rain upon us. These are the fences that funnel us, the traps that we get snagged in, the opportunities which alter things for the better, that we learn from, that introduce us to the people who help us and who abuse us. Here my life is a patchwork that is common for many of us. My pre-teen years were often disrupted with a chronic fight with asthma. The periods in hospital, out of school, fuelling a failure to settle and connect with other kids. But those periods also offered long stretches of time to read, and draw, and stare at things. Going into my teens I felt my ability to love change. At that moment the connection between desire and gender felt irrelevant. Looking back I see a messy, half-formed sense of bisexuality that was drip-fed in places and attacked in others. The openess in me was shattered by molesting advances I faced in the hands of a man who ran the firm that controlled the security for much of the retail and nightlife in the West End. It was years before I understood what this assault had done to me and the place of fear it had pushed me into when it came to male intimacy.

I remember that point when I wanted a treehouse. When so much of play is about making dens. Hideaways. Cosy, private spaces to take a little protection and let your world form and grow. I remember making little flat circles to lie somewhere in the long grass. Tiny structures out of cushions I could just put my head in and daydream. Sheets, blankets, cardboard and dusty corners. Books, stories, drawing and later music. My parents gave me many tools with which to make these spaces, kindling a creativity. Thinking back now I see the tree house as a metaphor for much of my childhood. It is rickety, patchy, the rain gets in and it doesn’t feel particularly safe. But the tree in which it sits is strong and sturdy. In my head that tree is my mother. So many of these lumps in life were soothed by her strength. She saw me early on and prepared me to be myself. I write this on a train, the window framing the drowsy green of England, and I remember sitting on a similar train with similar views, mum asking me what I was being called in the playground and did I know what those words meant. On that train she taught me a laundry list of abusive queer terms and told me that I should never let these words hurt me. That the people who used them knew nothing of love and little of themselves. I wish she had been right but they served the purpose the kids intended, to ostracise, to give short-term strength and immediate power to those bullying their way through the shitscapes of school. And in this lay another lesson. That no matter how much our kin love us, they cannot protect us from the pain that is one of the currencies of life.

Whatever school is, it hammers something into us. That kids now have had to become a little more understanding of the world of identity, violence, sex, climate catastrophe and so much else fills some adults with sadness at supposed lost innocence. It fills me with hope that those playgrounds I so hated have become a little softer. A little kinder. I see the space growing for increasingly younger people to move through their multitudes with more ease and grace and wonder. Their joy less clipped, their light less dimmed. Lives in which tarnished marks can be worked on, buffered with conversations and understanding. It is a sense of these planks and paths, bodies sliced and diced into whatever shape they become. Bodies of pain, hope and colours. This is what I try to summon with the pens, inks and paper I have used over the last few years. I have been lucky to have been given these spaces and chances to let myself out over the years. Every curious circumstance that my life has produced, from the bleakest to the most glorious is one I am grateful for. The people I’ve yet to become are here, alongside those that never materialized.